Atlas

Straight Street (Damascus) and surrounding region

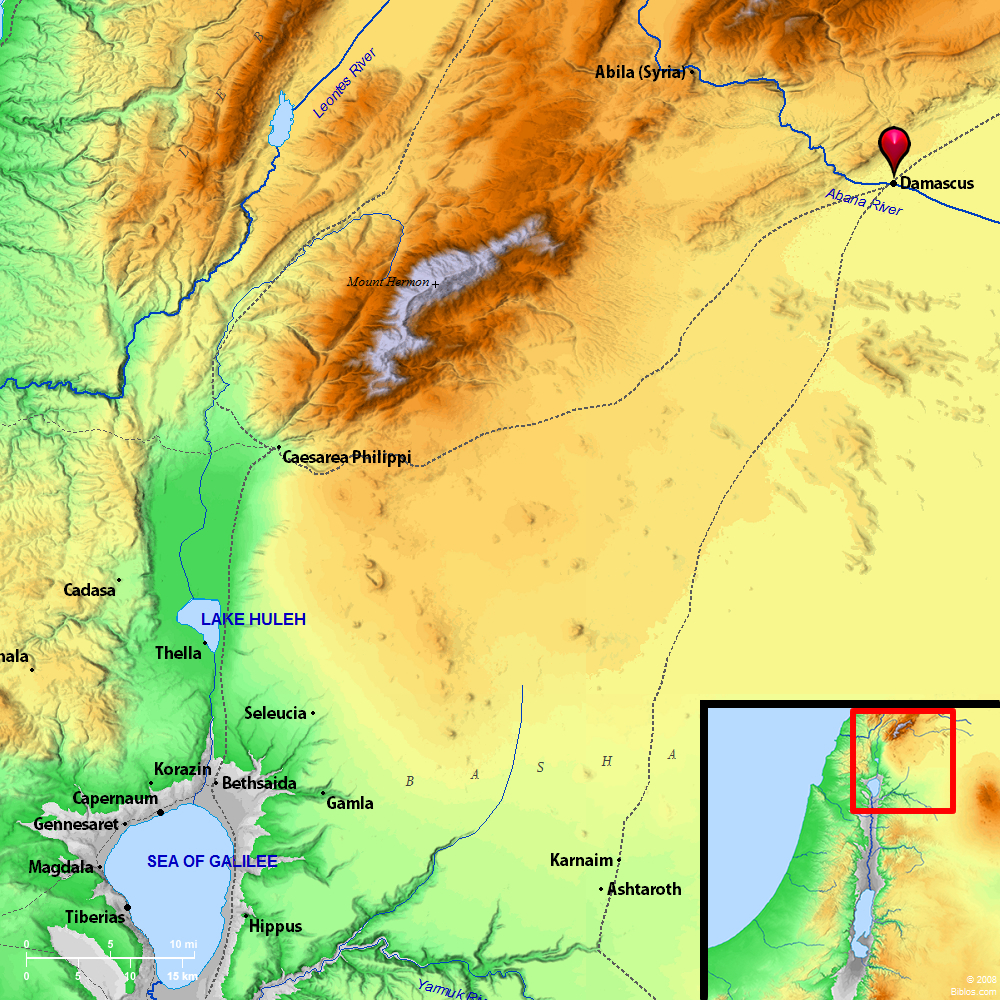

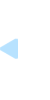

Maps Created using Biblemapper 3.0Additional data from OpenBible.info

You are free to use up to 50 Biblos coprighted maps (small or large) for your website or presentation. Please credit Biblos.com.

Occurrences

Acts 9:11 The Lord said to him, "Arise, and go to the street which is called Straight, and inquire in the house of Judah for one named Saul, a man of Tarsus. For behold, he is praying,

Encyclopedia

DAMASCUSda-mas'-kus:

1. The Name

2. Situation and Natural Features

3. The City Itself

4. Its History

(1) The Early Period (to circa 950 B.C.)

(2) The Aramean Kingdom (circa 950-732 B.C.)

(3) The Middle Period (732 B.C.-650 A.D.)

(4) Under Islam

1. Name:

The English name is the same as the Greek Damaskos. The Hebrew name is Dammeseq, but the Aramaic form Darmeseq, occurs in 1 Chronicles 18:5 2 Chronicles 28:5. The name appears in Egyptian inscriptions as Ti-mas-ku (16th century B.C.), and Sa-ra-mas-ki (13th century B.C.), which W. M. Muller, Asien u. Europa, 227, regards as representing Ti-ra-mas-ki, concluding from the "ra" in this form that Damascus had by that time passed under Aramaic influence. In the Tell el-Amarna Letters the forms Ti-ma-as-gi and Di-mas-ka occur. The Arabic name is Dimashk esh-Sham ("Damascus of Syria") usually contrasted to Esh-Sham simply. The meaning of the name Damascus is unknown. Esh-Sham (Syria) means "the left," in contrast to the Yemen (Arabia) = "the right."

2. Situation and Natural Features:

Damascus is situated (33 degrees 30' North latitude, 36 degrees 18' East longitude) in the Northwest corner of the Ghuta, a fertile plain about 2,300 ft. above sea level, West of Mt. Hermon. The part of the Ghuta East of the city is called el-Merj, the "meadow-land" of Damascus. The river Barada (see ASANA) flows through Damascus and waters the plain, through which the Nahr el-Awaj (see PHARPAR) also flows, a few miles South of the city.

Surrounded on three sides by bare hills, and bordered on the East, its open side, by the desert, its well-watered and fertile Ghuta, with its streams and fountains, its fields and orchards, makes a vivid impression on the Arab of the desert. Arabic literature is rich in praises of Damascus, which is described as an earthly paradise. The European or American traveler is apt to feel that these praises are exaggerated, and it is perhaps only in early summer that the beauty of the innumerable fruit trees-apricots, pomegranates, walnuts and many others-justifies enthusiasm. To see Damascus as the Arab sees it, we must approach it, as he does, from the desert. The Barada (Abana) is the life blood of Damascus. Confined in a narrow gorge until close to the city, where it spreads itself in many channels over the plain, only to lose itself a few miles away in the marshes that fringe the desert, its whole strength is expended in making a small area between the hills and the desert really fertile. That is why a city on this site is inevitable and permanent. Damascus, almost defenseless from a military point of view, is the natural mart and factory of inland Syria. In the course of its long history it has more than once enjoyed and lost political supremacy, but in all the vicissitudes of political fortune it has remained the natural harbor of the Syrian desert.

3. The City Itself:

Damascus lies along the main stream of the Barada, almost entirely on its south bank. The city is about a mile long (East to West) and about half a mile broad (North to South). On the south side a long suburb, consisting for the most part of a single street, called the Meidan, stretches for a mile beyond the line of the city wall, terminating at the Bawwabet Allah, the "Gate of God," the starting-point of the Haj, the annual pilgrimage to Mecca. The city has thus roughly the shape of a broad-headed spoon, of which the Meidan is the handle. In the Greek period, a long, colonnaded street ran through the city, doubtless the "street which is called Straight" (Acts 9:11). This street, along the course of which remains of columns have been discovered, runs westward from the Babesh-Sherki, the "East Gate."

Part of it is still called Derb el-Mustakim ("Straight Street"), but it is not certain that it has borne the name through all the intervening centuries. It runs between the Jewish and Christian quarters (on the left and right, respectively, going west), and terminates in the Suk el-Midhatiyeh, a bazaar built by Midhat Pasha, on the north of which is the main Moslem quarter, in which are the citadel and the Great Mosque. The houses are flat-roofed, and are usually built round a courtyard, in which is a fountain. The streets, with the exception of Straight Street, are mostly narrow and tortuous, but on the west side of the city there are some good covered bazaars. Damascus is not rich in antiquities.

The Omayyad Mosque, or Great Mosque, replaced a Christian church, which in its time had taken the place of a pagan temple. The site was doubtless occupied from time immemorial by the chief religious edifice of the city. A small part of the ancient Christian church is still extant. Part of the city wall has been preserved, with a foundation going back to Roman times, surmounted by Arab work. The traditional site of Paul's escape (Acts 9:25 2 Corinthians 11:33) and of the House of Naaman (2 Kings 5) are pointed out to the traveler, but the traditions are valueless.

The charm of Damascus lies in the life of the bazaars, in the variety of types which may be seen there-the Druse, the Kurd, the Bedouin and many others-and in its historical associations. It has always been a manufacturing city. Our word "damask" bears witness to the fame of its textile industry, and the "Damascus blades" of the Crusading period were equally famous; and though Timur (Tamerlane) destroyed the trade in arms in 1399 by carrying away the armorers to Samarcand, Damascus is still a city of busy craftsmen in cloth and wood. Its antiquity casts a spell of romance upon it. After a traceable history of thirty-five centuries it is still a populous and flourishing city, and, in spite of the advent of the railway and even the electric street car, it still preserves the flavor of the East.

4. Its History:

(1) The Early Period (to circa 950 B.C.).

The origin of Damascus is unknown. Mention has already been made (section 1) of the references to the city in Egyptian inscriptions and in the Tell el-Amarna Letters. It appears once-possibly twice-in the history of Abraham. In Genesis 14:15 we read that Abraham pursued the four kings as far as Hobah, "which is on the left hand (i.e. the north) of Damascus." But this is simply a geographical note which shows only that Damascus was well known at the time when Genesis 14 was written. Greater interest attaches to Genesis 15:2, where Abraham complains that he is childless and that his heir is "Dammesek Eliezer" (English Revised Version), for which the Syriac version reads "Eliezer the Damaschul." The clause, however, is hopelessly obscure, and it is doubtful whether it contains any reference to Damascus at all. In the time of David Damascus was an Aramean city, which assisted the neighboring Aramean states in their unsuccessful wars against David (2 Samuel 8:5 f). These campaigns resulted indirectly in the establishment of a powerful Aramean kingdom in Damascus. Rezon, son of Eliada, an officer in the army of Hadadezer, king of Zobah, escaped in the hour of defeat, and became a captain of banditti. Later he established himself in Damascus, and became its king (1 Kings 11:23). He cherished a not unnatural animosity against Israel and the rise of a powerful and hostile kingdom in the Israelite frontier was a constant source of anxiety to Solomon (1 Kings 11:25).

(2) The Aramean Kingdom (circa 950-732 B.C.).

Whether Rezon was himself the founder of a dynasty is not clear. He has been identified with Hezion, father of Tab-rimmon, and grandfather of Ben-hadad (1 Kings 15:18), but the identification, though a natural one, is insecure. Ben-hadad (Biridri) is the first king of Damascus, after Rezon, of whom we have any detailed knowledge. The disruption of the Hebrew kingdom afforded the Arameans an opportunity of playing off the rival Hebrew states against each other, and of bestowing their favors now on one, and now on the other. Benhadad was induced by Asa of Judah to accept a large bribe, or tribute, from the Temple treasures, and relieve Asa by attacking the Northern Kingdom (1 Kings 15:18). Some years later (circa 880 B.C.) Ben-hadad (or his successor?) defeated Omri of Israel, annexed several Israelite cities, and secured the right of having Syrian "streets" (i.e. probably a bazaar for Syrian merchants) in Samaria (1 Kings 20:34). Ben-hadad II (according to Winckler the two Ben-hadads are really identical, but this view, though just possible chronologically, conflicts with 1 Kings 20:34) was the great antagonist of Ahab. His campaigns against Israel are narrated in 1 Kings 20:22. At first successful, he was subsequently twice defeated by Ahab, and after the rout at Aphek was at the mercy of the conqueror, who treated him with generous leniency, claiming only the restoration of the lost Israelite towns, and the right of establishing an Israelite bazaar in Damascus.

On the renewal of hostilities three years later Ahab fell before Ramoth-gilead, and his death relieved Ben-hadad of the only neighboring monarch who could ever challenge the superiority of Damascus. Further light is thrown upon the history of Damascus at this time by the Assyrian inscriptions. In 854 B.C. the Assyrians defeated a coalition of Syrian and Palestine states (including Israel) under the leadership of Ben-hadad at Karqar. In 849 and 846 B.C. renewed attacks were made upon Damascus by the Assyrians, who, however, did not effect any considerable conquest. From this date until the fall of the city in 732 B.C. the power of the Aramean kingdom depended upon the activity or quiescence of Assyria. Hazael, who murdered Ben-hadad and usurped his throne circa 844 B.C., was attacked in 842 and 839, but during the next thirty years Assyria made no further advance westward. Hazael was able to devote all his energies to his western neighbors, and Israel suffered severely at his hands. In 803 Mari' of Damascus, who is probably identical with the Ben-hadad of 2 Kings 13:3, Hazael's son, was made tributary to Ramman-nirari III of Assyria. This blow weakened Aram, and afforded Jeroboam II of Israel an opportunity of avenging the defeats inflicted upon his country by Hazael. In 773 Assyria again invaded the territory of Damascus.

Tiglath-pileser III (745-727 B.C.) pushed vigorously westward, and in 738 Rezin of Damascus paid tribute. A year or two later he revolted, and attempted in concert with Pekah of Israel, to coerce Judah into joining an anti-Assyrian league (2 Kings 15:37; 2 Kings 16:5 Isaiah 7). His punishment was swift and decisive. In 734 the Assyrians advanced and laid siege to Damascus, which fell in 732. Rezin was executed, his kingdom was overthrown, and the city suffered the fate which a few years later befell Samaria.

(3) The Middle Period (circa 732 B.C.-650 A.D.).

Damascus had now lost its political importance, and for more than two centuries we have only one or two inconsiderable references to it. It is mentioned in an inscription of Sargon (722-705 B.C.) as having taken part in an unsuccessful insurrection along with Hamath and Arpad. There are incidental references to it in Jeremiah 49:23 and Ezekiel 27:18; Ezekiel 47:16. In the Persian period Damascus, if not politically of great importance, was a prosperous city. The overthrow of the Persian empire by Alexander was soon followed (301 B.C.) by the establishment of the Seleucid kingdom of Syria, with Antioch as its capital, and Damascus lost its position as the chief city of Syria. The center of gravity was moved toward the sea, and the maritime commerce of the Levant became more important than the trade of Damascus with the interior. In 111 B.C. the Syrian kingdom was divided, and Antiochus Cyzicenus became king of Coele-Syria, with Damascus as his capital. His successors, Demetrius Eucaerus and Antiochus Dionysus, had troubled careers, being involved in domestic conflicts and in wars with the Parthians, with Alexander Janneus of Judea, and with Aretas the Nabatean, who obtained possession of Damascus in 85 B.C. Tigranes, being of Armenia, held Syria for some years after this date, but was defeated by the Romans, and in 64 B.C. Pompey finally annexed the country.

The position of Damascus during the first century and a half of Roman rule in Syria is obscure. For a time it was in Roman hands, and from 31 B.C.-33 A.D. its coins bear the names of Augustus or Tiberius. Subsequently it was again in the hands of the Nabateans, and was ruled by an ethnarch, or governor, appointed by Aretas, the Nabatean king. This ethnarch adopted a hostile attitude to Paul (2 Corinthians 11:32 f). Later, in the time of Nero, it again became a Roman city. In the early history of Christianity Damascus, as compared with Antioch, played a very minor part. But it is memorable in Christian history on account of its associations with Paul's conversion, and as the scene of his earliest Christian preaching (Acts 9:1-25). All the New Testament references to the city relate to this event (Acts 9:1:25; Acts 22:5-11; 26:12, 20 2 Corinthians 11:32 Galatians 1:17). Afterward, under the early Byzantine emperor, Damascus, though important as an outpost of civilization on the edge of the desert, continued to be second to Antioch both politically and ecclesiastically. It was not until the Arabian conquest (634 A.D. when it passed out of Christian hands, and reverted to the desert, that it once more became a true capital.)

(4) Under Islam.

Damascus has now been a Moslem city, or rather a city under Moslem rule, for nearly thirteen centuries. For about a century after 650 A.D. it was the seat of the Omayyad caliphs, and enjoyed a position of preeminence in the Moslem world. Later it was supplanted by Bagdad, and in the 10th century it came under the rule of the Fatimites of Egypt. Toward the close of the 11th century the Seljuk Turks entered Syria and captured Damascus. In the period of the Crusades the city, though never of decisive importance, played a considerable part, and was for a time the headquarters of Saladin. In 1300 it was plundered by the Tartars, and in 1399 Timur exacted an enormous ransom from it, and carried off its famous armorers, thus robbing it of one of its most important industries. Finally, in 1516 A.D., the Osmanli Turks under Sultan Selim conquered Syria, and Damascus became, and still is, the capital of a province of the Ottoman Empire.

C. H. Thomson